My friends will become nothing.

I too will become nothing.

Likewise all will become nothing.

Just like a dream experience,

Whatever things I enjoy

Will become a memory.

Whatever has passed will not be seen again.

Even within this brief life

Many friends and foes have passed,

But whatever unbearable evil I committed for them

Remains ahead of me.

- Shantideva, Bodhisattvacharyavatara, II(35-37)

that one day we all must die.

But those who do realize this settle their quarrels.

- Dhammapada, verse 6

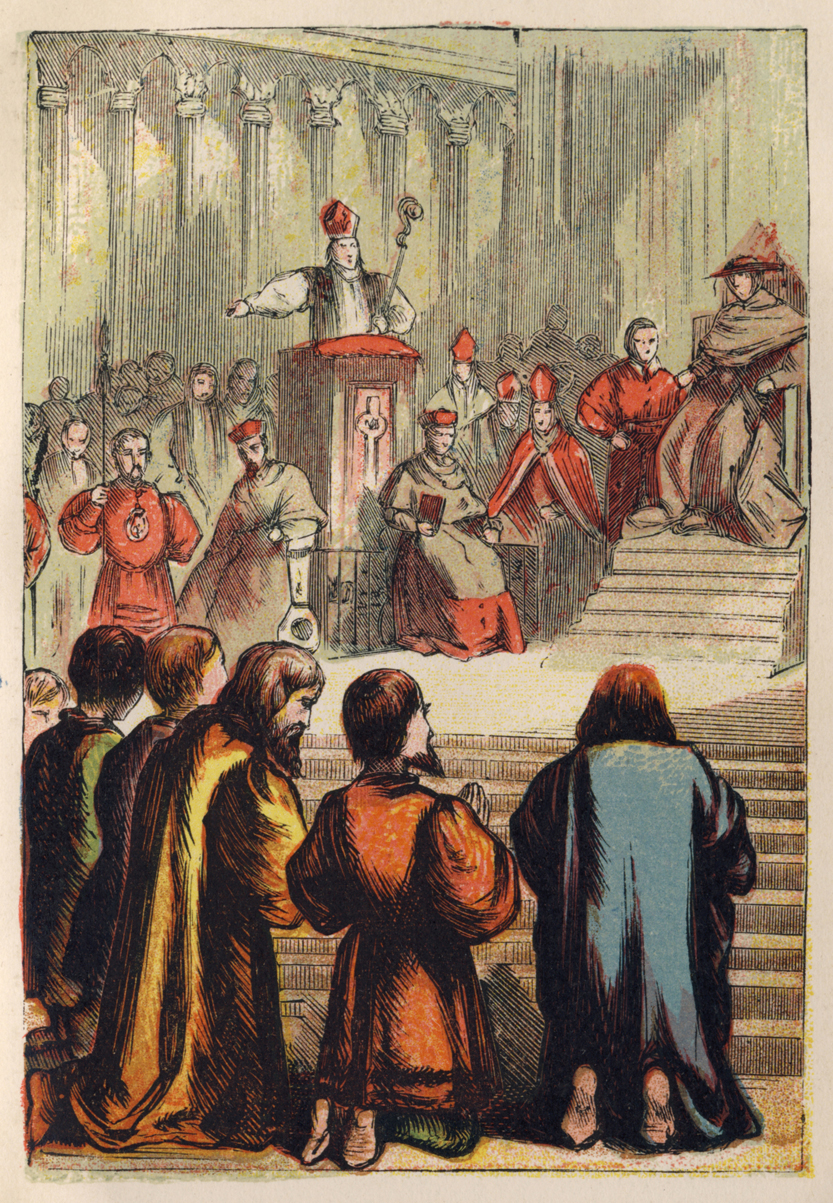

Barnes and his Fellow Prisoners Seeking Forgiveness

Joseph Martin Kronheim, 19th century

My dear friends,

Forgiveness is a universal spiritual theme, emphasized in both Christian and Buddhist traditions. Whether we seek forgiveness from God, from others, or from ourselves, we begin a process of release—liberating the heart from resentment, guilt, and sorrow. In both traditions, the act of forgiveness is not merely an obligation but a profound expression of compassion and wisdom. However, this path often feels challenging, as it requires not only humility but also a realization of our interconnectedness and impermanence. Let us reflect on how these two traditions guide us in the practices of forgiveness and acceptance.

In Buddhism, the realization of impermanence softens the heart, making forgiveness a natural outflow of wisdom. When we truly grasp that all beings—whether friends or enemies—are subject to change and death, the futility of holding grudges becomes apparent. The teachings of Shantideva remind us that whatever harm we inflict on others remains in our karma, awaiting us until we seek forgiveness and offer it to others. The Dhammapada reinforces this, showing that those who grasp impermanence let go of their disputes. Forgiveness in this sense becomes a gift we offer to both ourselves and others as we awaken to the fleeting nature of life.

"What if Joseph still bears a grudge against us

and pays us back in full for all the wrong that we did to him?"

So they approached Joseph, saying,

"Your father gave this instruction before he died, 'Say to Joseph:

I beg you, forgive the crime of your brothers and the wrong they did in harming you.'

Now therefore please forgive the crime of the servants of the God of your father."

Joseph wept when they spoke to him.

Then his brothers also wept, fell down before him, and said, "We are here as your slaves."

But Joseph said to them, "Do not be afraid! Am I in the place of God?

Even though you intended to do harm to me, God intended it for good,

in order to preserve a numerous people, as he is doing today.

So have no fear; I myself will provide for you and your little ones."

In this way he reassured them, speaking kindly to them.

- Genesis 50:15-21

In the story of Joseph, we witness the transformative power of forgiveness in the face of deep betrayal. Joseph, wronged by his brothers, could have responded with anger, but he chose to forgive, seeing the divine purpose in his suffering. His forgiveness is not just an act of personal release but an embodiment of trust in God's greater plan. Similarly, in our spiritual journey, forgiveness allows us to transcend personal grievances and align with a higher will, trusting that even in the harms done to us, there may be opportunities for growth, reconciliation, and healing.

"Lord, if another member of the church sins against me, how often should I forgive?

As many as seven times?"

Jesus said to him, "Not seven times, but, I tell you, seventy-seven times.

"For this reason the kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king

who wished to settle accounts with his slaves.

When he began the reckoning, one who owed him ten thousand talents was brought to him,

and, as he could not pay, the lord ordered him to be sold,

together with his wife and children and all his possessions, and payment to be made.

So the slave fell on his knees before him, saying, 'Have patience with me, and I will pay you everything.'

And out of pity for him, the lord of that slave released him and forgave him the debt.

But that same slave, as he went out,

came upon one of his fellow slaves who owed him a hundred denarii,

and seizing him by the throat he said, 'Pay what you owe.'

Then his fellow slave fell down and pleaded with him, 'Have patience with me, and I will pay you.'

But he refused; then he went and threw him into prison until he would pay the debt.

When his fellow slaves saw what had happened, they were greatly distressed,

and they went and reported to their lord all that had taken place.

Then his lord summoned him and said to him,

'You wicked slave! I forgave you all that debt because you pleaded with me.

Should you not have had mercy on your fellow slave, as I had mercy on you?'

And in anger his lord handed him over to be tortured until he would pay his entire debt.

So my heavenly Father will also do to every one of you,

if you do not forgive your brother or sister from your heart."

- Matthew 18:21-35

Jesus' teaching on forgiveness sets no limits. The parable reminds us that our own capacity to receive grace depends on our willingness to extend it. Just as the king forgave the enormous debt of his servant, we too are called to forgive endlessly, knowing that we have been forgiven much. In this way, forgiveness in Christianity is not conditional or transactional—it is a profound act of love that mirrors divine mercy. Jesus invites us to transcend our natural inclination toward revenge or justice and embody the boundless compassion that flows from God's heart.

Some believe in eating anything, while the weak eat only vegetables.

Those who eat must not despise those who abstain,

and those who abstain must not pass judgment on those who eat,

for God has welcomed them.

Who are you to pass judgment on slaves of another?

It is before their own lord that they stand or fall.

And they will be upheld, for the Lord is able to make them stand.

Some judge one day to be better than another, while others judge all days to be alike.

Let all be fully convinced in their own minds.

Those who observe the day, observe it for the Lord.

Also those who eat, eat for the Lord, since they give thanks to God;

while those who abstain, abstain for the Lord and give thanks to God.

For we do not live to ourselves, and we do not die to ourselves.

If we live, we live to the Lord, and if we die, we die to the Lord;

so then, whether we live or whether we die, we are the Lord's.

For to this end Christ died and lived again,

so that he might be Lord of both the dead and the living.

Why do you pass judgment on your brother or sister?

Or you, why do you despise your brother or sister?

For we will all stand before the judgment seat of God.

- Romans 14:1-10

Think not about whatever is seen in others.

- Geshe Chekawa, Mind Training in Seven Points, 6.3-4

In both Romans and Geshe Chekawa’s "Mind Training," the act of not judging others becomes a means of cultivating compassion and patience. We are all on unique spiritual journeys, and our actions, influenced by various factors, should not be sources of condemnation. When we abstain from judgment, we open the door to acceptance. In doing so, we reflect God's acceptance of all people, regardless of their spiritual weaknesses or differences. In Buddhism, refraining from judgment aligns with the practice of equanimity and loving-kindness, extending compassion to all beings without attachment to their flaws or imperfections.

Both the Christian and Buddhist traditions offer profound insights into the practices of forgiveness and acceptance. These teachings ask us to transcend our egoic need to be right, to retaliate, or to harbor resentment. Forgiveness becomes an act of release—freeing ourselves and others from the chains of past harm. Acceptance, likewise, acknowledges the imperfections and humanity in ourselves and others without the need for judgment. When we follow these practices, we move closer to embodying the Bodhisattva wisdom and compassion of Christ, leading to a life of peace and reconciliation.

The Heart of the Matter